Falun Gong Practitioners Systematically Murdered for Their Organs: Refuting the Chinese Regime's "Death Row" Explanation, Chapter IV

(Minghui.net) In 2006, The Epoch Times newspaper broke a stunning story about what is undoubtedly one of the most horrible atrocities to be committed by any government, not only in modern times, but in all of recorded history. As documented in the investigative report, "Bloody Harvest," by noted human rights lawyer David Matas and former Canadian Secretary of State for the Asia-Pacific region David Kilgour, there is overwhelming evidence of the Chinese Communist regime's chilling role in systematically murdering Falun Gong practitioners, harvesting their organs while they are alive, and making huge profits from doing so. In response to the international outcry, the Chinese regime has attempted to explain away one of the main pieces of circumstantial evidence--the meteoric rise in the number of organ transplantations in recent years and the extremely short wait times in a culture notoriously averse to organ donation--by stating that it has harvested organs from executed criminals after their deaths. Faced with undeniable evidence, it has attempted to escape culpability for a monstrous atrocity by admitting to a lesser crime. In this report, we will show evidence that directly contradicts this claim and lends further credence to the serious charges leveled against the Chinese regime.

In this section, we will explain why we are assuming that the number of death row inmates with organs suitable for transplantation is 30% the total.

1. Tissue matching - a bottleneck with death row "donors"

In Chapter II and Appendix 1, we have shown that HLA matching is extremely complex. There are seven groups of HLA, with a total of 148 antigens. The possible permutations number well over 2,000,000. Except for twins from the same egg, it is practically impossible to locate a supplier and a recipient with identical HLA. As a result, rejection reaction always follows a homograft. It has to be treated with intense immune suppression. The probability of unrelated people meeting minimum matching HLA requirements (for immunosuppressant drugs to be effective after transplantation) is between 20-30%. Thus, the percentage of death row inmates with matching organs cannot exceed 30% with any significant sample size.

2. Critical time window dictated by cold ischemia

When an organ leaves the human body, the tissue will break down. When a person's heart stops beating, his or her organs will be useful for a 15-minute window, and must be procured promptly and preserved by a special medium at very low temperatures. Even under optimal conditions, the organ must be transplanted within a critical time window because of cold ischemia (cooling of an organ with a cold perfusion solution after organ procurement surgery). With current technology, the critical time window is 24 hours for a kidney, 15 hours for a liver, and 6 hours for a heart. Therefore, in addition to tissue matching, cold ischemia is a second critical restraint. It is simply not yet possible to preserve organs suitably for future needs.

In addition to these technical limitations, there are other important considerations when using organs from death row inmates that will be explained below.

3. Death row inmates' organs, a one-time resource

Organs from death row inmates are a one-time resource. Unlike organs hosted by a pool of living people, organs from death row inmates cannot be reserved for future use. Of course, there are reports that some courts have stayed executions until the hospital found a matching recipient. However, in most cases, executions of death row inmates are a political act for the Chinese Communist regime to maintain its power, and therefore, not every execution can be put on hold for medical reasons. For example, due to perceived political needs, the Chinese Communist regime makes a habit of executing death row inmates on national holidays, such as New Year's Day, May Day, or National Day, to get the most exposure from the event. Quite often, the dictated times of such executions mean that the inmates' organs are not used. Wang Guoqi, formerly a burn specialist at the Paramilitary Tianjin General Hospital in Tianjin, testified before the Subcommittee on International Operations and Human Rights of the United States House of Representatives. In a written statement he stated, "I have removed skin from the corpses of executed prisoners," and further described how he went to the places of execution to remove the organs. Among four inmates executed, only one was a match for organs. Dr. Wang was told to take the corpse to an ambulance within 15 seconds of the gunshot. He and another doctor then took 13 seconds to remove the skin. [21]

4. Factors limiting death row inmate organs

Execution of death row inmates happens in different locations and at various times. Since China does not have an organ sharing network, such as the United Network for Organ Sharing in the United States, the tissue matching of organs from the executed inmates can only take place in or near the area of execution. Therefore, death row inmates are considered a rare resource. Some scholars have pointed out that local courthouses often team up with the local hospitals to protect local interests. This phenomenon makes it much harder for hospitals outside the area to get access to organs. It was not until August 2009 that China announced an experimental organ donation system in ten selected provinces and cities.

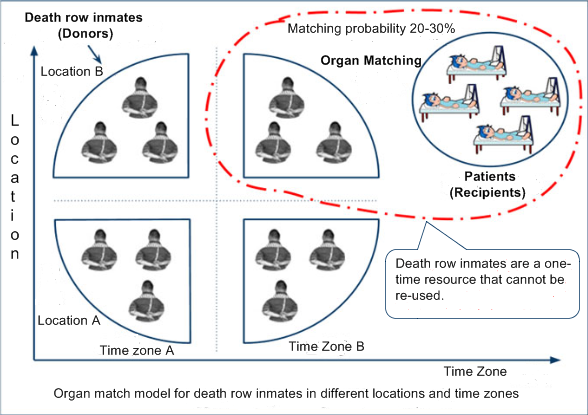

The following chart illustrates how death row inmates can be divided into four different groups based on their location and times of execution. In principle, in any given location at any given time, the organs from the executed death row inmates can only be matched with the patients in that specific location at that specific time. Thus, the number of wasted organs is likely to be very high.

For this reason, we fear that detained Falun Gong practitioners have become a reservoir for large scale matching and live organ harvesting, which we will discuss in later sections.

5. Harvesting of death row inmate organs follows the "court-driven model"

On October 9, 1984, China's Supreme People's Court, Supreme People's Procuratorate, Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Public Health, and Ministry of Civil Affairs promulgated and implemented the "Interim Provisions on Using Cadavers or Organs from the Cadavers of Death Row Inmates," providing legal authority for using organs from executed death row inmates.

While the court, the procuratorate, the detention center, and the hospital are integral parts of the process to harvest the death row inmates' organs, the key party is the court, since it hands down the death sentences and carries out the executions. Prior to execution, the death row inmate is required to undergo blood tests with approval from the detention center. Then the court carries out the execution under the procuratorate's supervision. Both the court and the procuratorate restrict access to the execution site and assist the doctors in harvesting organs from the executed inmates. The Chinese Communist government adopted this process when China's organ transplant market was in its earliest stage and introduced the aforementioned 1984 Interim Provisions to give the process legal authority. It has been following this process since. Phoenix Weekly (number 21, 2005) quoted a source as saying, "Without the Justice Department's approval, it would be impossible for hospitals to harvest organs from executed death row inmates." [22]

The courts play a key role in procuring organs from executed death row inmates

The court-driven model renders the process of using organs from executed death row inmates a rather public, programmed, and sometimes even bureaucratic one, in which the court, the procuratorate, the detention center, and the hospital play integral roles with their own interests in mind. This process is known to human rights watchers, despite the Chinese Communist government's consistent denials until recent years (see Preface). It should be made clear that doctors cannot simply go to the detention center and ask the prison guards for executed death row inmates to harvest the organs. The more parties and steps involved, the less efficient the process of organ harvesting.

6. Legal requirements for an "unclaimed bodies" classification

The 1984 Interim Provisions provided the following guidelines for accepting organs from unclaimed cadavers or those from executed inmates; the guidelines stipulate that cadavers are acceptable if:

-

They are unclaimed or refused by the family of the executed;

-

They are voluntarily donated by the death row inmates;

-

Family of the executed gives consent.

Inevitably, driven by potentially huge financial benefits, some people have found ways to exploit loopholes in these guidelines. For example, in some cases, families were not notified of the time of execution and the bodies remained unclaimed as a consequence. Nevertheless, these guidelines do impose legal restrictions on the use of death row inmate's organs.

Reactions from families of the executed to the embezzlement of death row inmate organs

Since 2000, families of executed inmates have openly complained about the removal of organs without consent. Some have even filed lawsuits. This has increased the uncertainty surrounding the use of death row inmates' organs.

In September 2000, Yu Yonggang from Taiyuan City, Shanxi Province was sentenced to death for robbery and murder. Yu's mother repeatedly stated that the hospital and the court had taken away her son's organs without her consent. She wrote a letter entitled "A Citizen's Tearful Complaint" to bring the matter out into the open, pointing fingers at the relevant government bodies.

In May 2000, Fu Xingrong, a farmer from Jiangxi Province, was executed for murder. The local court sold his kidneys to one of the major hospitals in Jiangxi Province without Fu's family's consent. Out of grief and indignation, Fu's father committed suicide. Fu's sister hired an attorney and filed a lawsuit against the local court.

On September 23, 2003, Lanzhou Morning News reported a case in which a detention center in Gansu Province had "donated" organs from an executed death row inmate without his consent. The local court later ruled that the detention center must pay the family 2,000 yuan as compensation. The director of the detention center admitted to the media that organ donation must have written consent from the death row inmate, and that the detention center did not have any written document from the inmate in this case. [23]

The reactions of families such as these have created hesitation about the use of death row prisoners' organs, at least to a certain degree, and at this time, death-row-derived organs can no longer be considered a broad and readily-available resource.

Other considerations include age (ideally, the 'donor' should be between 20 and 30) and health status. Many inmates are addicted to cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs, which makes them less than ideal donors.

All of this explains the relatively low percentage of potentially useful organs that can be derived from death row "donors." We have discussed how a poorly matched organ directly impacts the quality of the transplant surgery. If a high number of patients were to die on the operating table or have a short survival time after the surgery, it directly impacts the surgeon's reputation and career. It stands to reason, then, that the transplant surgeon prefers not to use a randomly sourced organ in surgery. In summary, we consider a figure of 20-30% suitable organs derived from death row inmates a reasonable, if not optimistic, estimate, and in our calculations, we have settled on the 30% figure as the upper limit.

Due to these limitations on the use of death row prisoners' organs, the annual number of organs from executed inmates is probably around 6,000. Yet, between 2003 and 2006, there was a massive growth in China's organ transplant market. Clearly death row prisoners' organs alone did not meet this skyrocketing demand.

References

[21] Wang Guoqi, "I have removed skins from the corpses of executed prisoners - testimony by Wang Guoqi, a surgeon at the Tianjin Armed Police Corps Hospital," cited from The World Journal at http://www.chinamonitor.org/news/qiguang/wqgzb.htm

[22] Phoenix Weekly (number 21, 2005), "Investigation of Organ Donation from Death Row Inmates," http://www.ifeng.com/phoenixtv/72951501286277120/20050823/617113.shtml

[23] Deng Fei, "Investigation of Organ Donation from Death Row Inmates," Phoenix Weekly, http://health.sohu.com/20081120/n260760080.shtml